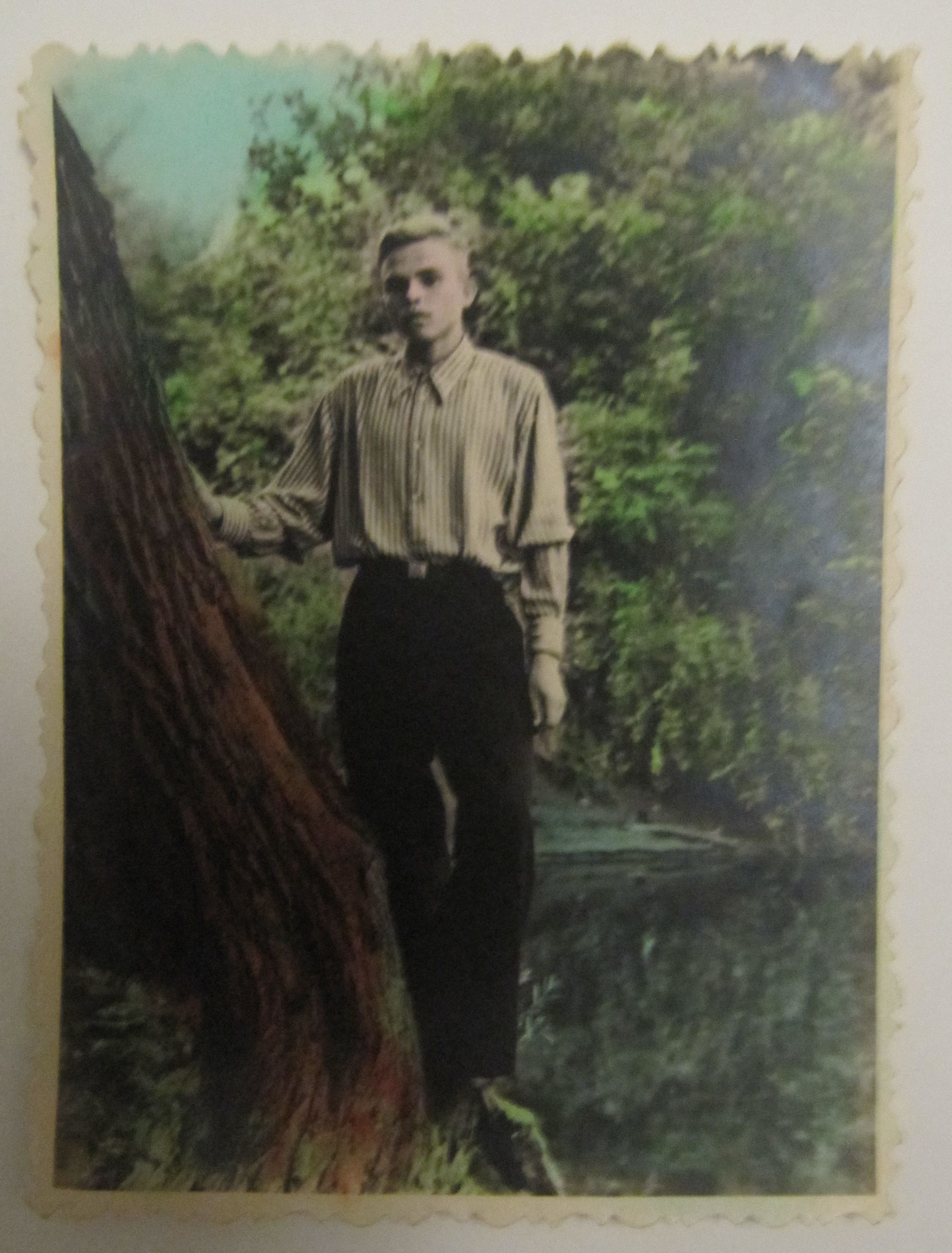

In the industrial age, nature [priroda] was understood widely as both a resource for industry and for leisure. Landscape photography was a globally popular genre too. In these photos, nature often reflected the subject’s mood. It was a romantic projection of their inner world. The introduction of industry into these photos initially communicated ideas of harmony and no friction. Chimneys are surrounded by greenery, while miners’ settlements bloom with rose bushes. People swim in rivers and lakes used for manufacturing.

Azovstal Panorama, view from the sea, 1949. Photo: Pavlo Kashkel/ Mariupol Local History Museum

Portrait in nature, Druzhkivka, late 1950s. Source: family archive of Dmytro Bilko

Since mass industrialization took place much later in Eastern as opposed to Western Europe, the appeal of pictures of smoking chimneys and powerful furnaces lasted a generation or two longer. However, the mismatch between these photographs and people’s lived experience became increasingly obvious over time.

Krasnolymanska mine, 1990s. Photo: Mykola Bilokon/Pokrovsk Historical Museum

The destructive impact of ever-expanding economic growth was already clear in the 1950s. Humans’ “victory over nature” was clearly Pyrrhic, and was one that endangered the health and life of the victors. The gradual development of ecological awareness took place in the context of a relentless competition between the Soviet Union and the capitalist West. This competition was not only about how much each side produced but also about which of them protected nature and people’s health better. In the postwar decades, the Soviet Union often endorsed a discourse of comparison: the USSR spread the idea that capitalist countries could not control private companies adequately, and was not able to ensure that they cared for the environment. In the 1970s détente between the opposing sides of the Cold War meant Soviet professionals had more opportunities to participate in international research projects and knowledge exchange. This exposure and the fact that state-run enterprises were not willing to control production led to greater critical engagement with their domestic conditions. Some Soviet dissident movements endorsed strong ecological agendas too. Although the Soviet Union promoted techno-optimism, it was entering an era of new environmental awareness.